The Amstrad CPC 464

History

Amstrad was a large consumer electronics manufacturer in the UK with various product lines but in the early 1980s they were noted particularly for producing inexpensive hi-fi equipment. Whilst rarely fondly remembered for the audio fidelity of their products, their expertise lay in delivering value-for-money bundle deals at prices affordable to the masses.

Amstrad boss, Alan Sugar, had initially dismissed personal computers as a passing fad, but on seeing the success of Sinclair, Acorn and Commodore in the UK, and faced with declining profit margins for existing product ranges, he changed his mind and decided that Amstrad should have a piece of the growing market.

Amstrad saw computers as just another consumer product category, no different to a toaster or a television. Perhaps not incorrectly, Sugar thought the most important aspect of a product was the average customer’s first impression on viewing it in a store. In his more colourful straight-talking parlance, this philosophy was reputedly distilled into the more pithy phrase ‘a mug’s eyefull’. To this end, Amstrad had gone about designing a plastic case before enough real consideration had been given to what electronics or software might go inside it and the computer itself was more of an afterthought. The CPC could easily have been a forgettable machine except that, through fortuitous circumstance, Amstrad hired exactly the right team.

An initial false start at finding a company to develop the electronics caused Amstrad to commit to purchasing a large selection of parts, including MOS 6502 processors, and the design needed to be ready for production by the end of 1983 for release in 1984. When that first partnership fell through in August 1983, long time Amstrad product developer, Bob Watkins, went to visit William Poel at Ambit International, an electronics company they had previously successfully worked with in the hope they might be able to rescue the project. Whilst sounding like a major conglomerate, it was in fact a modest operation with a shop in Essex that sold mail order electronic components and offered some contract engineering services.

At the exact time Watkins strode in, Poel’s friend, Roland Perry, was also there. Perry was an experienced computer engineer and had just recently developed a computerised stock control system for the company. Watkins showed Poel and Perry the case Amstrad had come up with together with the list of parts they had committed to purchasing and they were somehow convinced to take on the job of producing a system to fit within all of the constraints.

Ambit needed someone to take charge of the software. Through a contact at Acorn, Perry was put in touch with Locomotive Software, a tiny company then consisting of Richard Clayton and Chris Hall who were working out of a back bedroom.

A competitive 1980s home computer needed a BASIC implementation. Alan Sugar had already dismissed any suggestion of including the market leader, Microsoft BASIC, due to the licensing costs. Clayton estimated that writing a BASIC for the CPC using the 6502 would take him eight months, which was far outside of Amstrad’s tight schedule. However, he already had a BASIC completed for the Zilog Z80 that had been originally written for an Acorn product. Despite Amstrad having committed to buying the 6502 in bulk, Watkins was convinced to switch to the Z80 to expedite the project. The problem of the outstanding large components order was resolved by purchasing the new parts from the original suppliers, smoothing over the loss of the first order.

Clayton happened to know a good electronics designer, Mark-Eric Jones, also known as Mej, who knew the Z80 inside out. Mej joined the team, together with his business partner Roger Hurrey, and the pair would be instrumental in many aspects of the CPC hardware design. During his Amstrad years, Mej would develop a number of chip design tools. Later iterations of these were sold to Mentor Graphics, one of the world’s largest chip design companies (later bought by Siemens).

Perry knew that without applications, the machine would never sell and it would be a challenge to get retailers to accept it. He set about trying to convince developers to write for the platform and particularly so games, which he knew would be the driving force behind sales. Perry persuaded Amstrad to set up an initial publishing house, to be called ‘Amsoft’, to seed the market with a few dozen titles such that prospective CPC purchasers could see there was something available to buy at launch. This would hopefully bootstrap the market, bringing other publishers onboard. He also astutely delivered extensive support and dozens of prototype machines to developers while offering to extend the services of Amstrad’s marketing muscle to introduce them to major retailers, who could showcase their software to a wide audience.

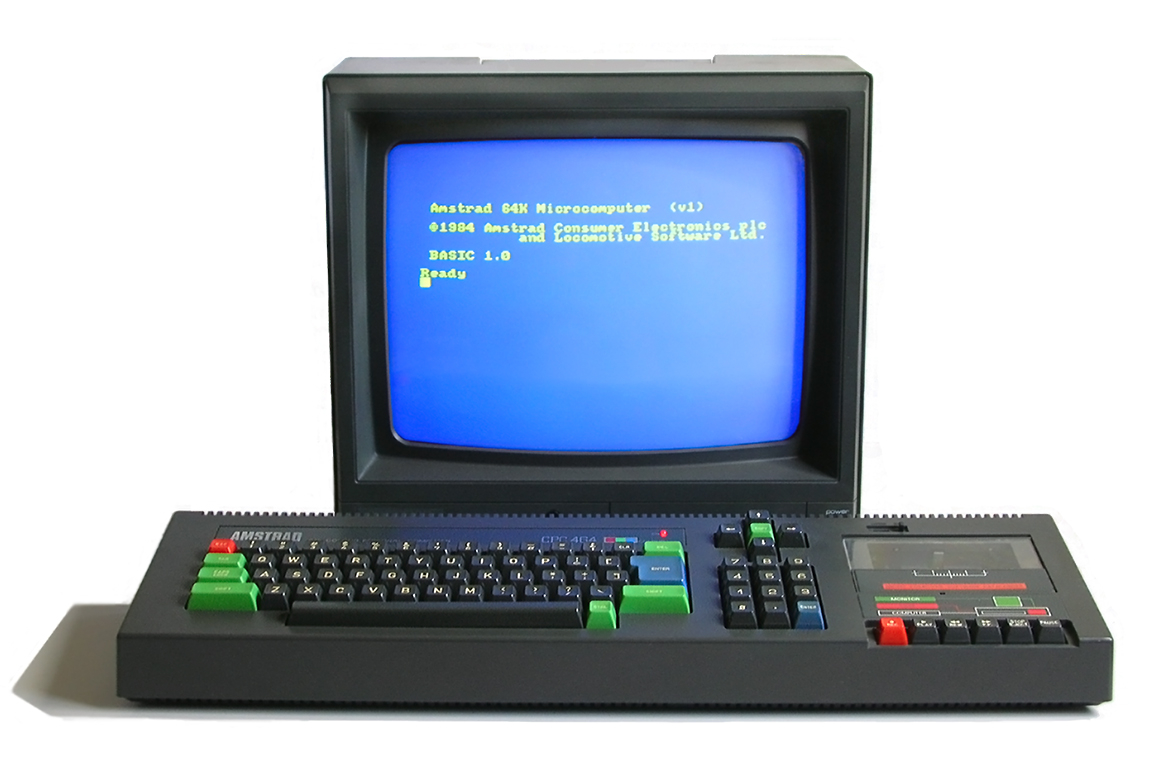

The Amstrad product concept was to follow the pattern of many of their previous successes and deliver a value bundle with a complete system. This consisted of not just the computer but also a monitor and cassette recorder. Sugar reasoned that freeing up the family TV through supplying a monitor might be popular with the adults purchasing the computer, but also would lead to higher usage of the system by younger users. Higher usage could of course in turn lead to greater sales of software and peripherals.

The end result was two CPC 464 offerings: a monochrome version at £249 and a package with a colour monitor at £349. Compared with the competition, these represented a very good deal with alternatives charging the same or more for the computer alone. Amstrad also bundled 12 software titles, including “Roland on the Ropes” and “Roland in the Caves”, thought to be named in honour of Roland Perry’s contribution to the machine.

The styling of the CPC was sometimes derided in contemporary magazines but this is possibly a misunderstanding of Amstrad’s target market. Reviewers, who were doubtlessly already very familiar with computer technology, perhaps had an IBM 5150 or the newly released Apple Macintosh in mind but these were the wrong comparisons to make.

When the CPC was designed in 1983, the average person rarely encountered a computer and probably didn’t even have access to one at work. The few everyday places where computers might be observed by the general public included locations such as banks and travel agents. Operators in these businesses would likely actually be using terminals connected remotely to some unseen mainframe or mini-computer, but from the perspective of the customer the terminal was the computer. The boxy industrial package and colourful keys of the CPC borrowed from the design language of these various anonymous terminals to convey a professional impression to the casual buyer, especially when the machine was displayed next to a Spectrum 48K on a store shelf.

Amstrad’s marketing approach combined with Perry’s drive and a superlative team of engineers turned the CPC into a very competent and well regarded computer. Everything had come together perfectly and diligence was rewarded with decent sales. Both in the UK and other European countries, around 3 million units shipped of all CPC models combined.

Ultimately one of Amstrad’s main rivals in the marketplace, Sinclair, entered financial difficulties. Amstrad bought out the Sinclair computer business in 1986 and ended up producing further iterations of the ZX Spectrum under the Sinclair brand. The Sinclair Spectrum +2 somewhat resembled the CPC and if the user ever removed the cover, they would see Amstrad emblazoned on the PCB.

Specifications

The Zilog Z80 used in the CPC was perhaps just slightly past its peak as a first class home computer CPU at the time of the machine’s release in 1984, but was still quite viable for a low-end machine and extensively used. It ran at 4Mhz but, as was a fairly common design compromise, it regularly yielded the bus to the video circuitry. An alternative figure of 3.3Mhz is sometimes seen, which is an estimate of an ‘effective’ clock rate if the CPU had continuous access to the bus.

As the ‘464’ moniker implies, the CPC contained 64KB of RAM, with the initial ‘4’ being the Amstrad product category indicator. This amount of memory was competitive with other machines in the same price bracket.

The CPC 464 was exported to Spain, but in 1985 the Spanish government mandated that all computers containing 64KB of RAM or less must have a Spanish keyboard, which the CPC did not. Amstrad’s response to this was to introduce the CPC 472, which contained 72KB of memory and was therefore exempt. However, on careful inspection owners will discover the extra 8KB of RAM doesn’t actually do anything and is in fact not even connected up! The memory chips may as well have been duct taped to the case and are simply present to satisfy the Spanish import requirements.

Video was delivered by a combination of a Motorola 6845 and a custom chip implemented as a gate array. The 6845 is not a complete video solution and doesn’t prescribe any particular video modes or generate a video signal. The chip is concerned with calculating video memory addresses and some aspects of CRT timing, with the gate array actually producing the video signal.

The Amstrad CPC supported 16 on-screen colours from a palette of 27, surpassing the capabilities of most competing low-cost machines. Beyond quantity, its colours were distinct and artist-friendly - qualities not always found in rivals. Unlike the Sinclair Spectrum, each pixel’s colour could be individually addressed, eliminating the issue of colour clash. The superior colour handling was likely the machine’s most innovative hardware feature. It impressed developers and also gave the CPC a clear visual edge in store displays, making its advantages immediately apparent even to inexperienced buyers.

Three video modes were offered, 160x200 pixels at 16 colours, 320x200 at 4 colours and 640x200 at 2 colours. The highest resolution mode could support 80 text columns which was often a requirement for business software and the mode was unavailable on many other machines.

The system implemented hardware scrolling, however, it was more aimed at text than games because it shifted the screen in whole bytes whereas one graphics pixel was represented at a granularity of only bits to save memory. The feature was exploited in many games but uptake from developers was intermittent as it didn’t always produce an acceptably smooth scrolling effect. While some coders figured out tricks for finer control, that wasn’t a simple matter for the average developer to achieve. The later CPC Plus would have an improved hardware scroll feature more readily suited to games.

Since the CPC shipped with an included monitor, a UHF interface was not required and the only video output was RGB. This presented a crisper image than Sinclair machines that used a television via RF for display. Unusually, presumably as a cost saving measure, the computer’s power supply was in the monitor and the system included a cable to draw power from a front facing connector on the screen.

Audio was supplied by the commonplace three channel General Instruments AY-3-8912 chip that was widely used on other systems. Each channel could produce a square wave or noise with envelope. It was not as sophisticated as the competing Commodore 64, but far superior to the Spectrum and within the bounds of expectations for the time. There was also a centronics printer port and a joystick connector.

Storage was via an integrated tape recorder. A helpful side-effect of the bundled tape machine was that the gain settings were pre-configured, which was useful to new computer users. On competing machines that used an external tape deck it could sometimes be troublesome to find the right audio levels to load a tape. No disk interface was included with the machine, although one was soon available as an add-on and later models would include the interface and a drive.

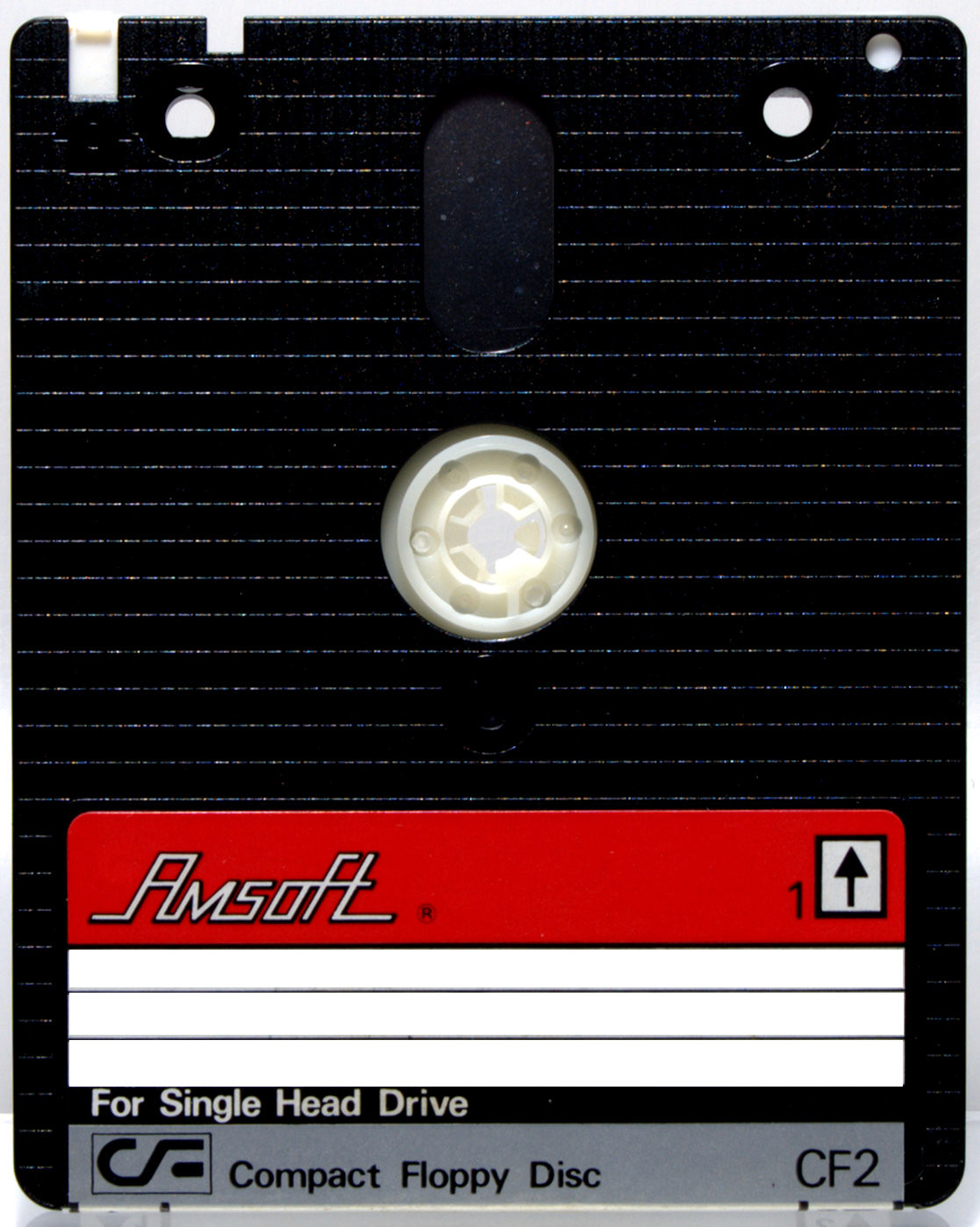

CF2 Disk System

The DDI-1 floppy disk system for the CPC was available in autumn 1984 as an optional extra and a floppy drive would be integrated into later models of the machine. The previous 5.25 inch ‘minifloppy’ format was now on the way out and smaller disks were the latest technology. However, the CPC did not use the soon to be ubiquitous Sony 3.5” disks. There were at the time multiple competing, now forgotten, disk formats vying to become the industry standard and Amstrad went with the 3” CF2 offering from the Matsushita consortium, which also included Hitachi.

The CF2 became very much the Betamax of the competing smaller disk formats. It had some benefits - most notably, its robust, hard-shelled disks. I used CF2s for many years and always found them to be quite reliable compared with the Sony 3.5” disks, but only a handful of other non-Amstrad computer systems ever adopted them.

There were rumours that Amstrad selected the CF2 because they somehow acquired an over-produced batch of the less popular drives at a discount price but this isn’t obviously true. The Amstrad drive was released at about £160 for the bare drive (or £199 with the required controller and CP/M) which was certainly a decent deal but it was more likely the case that the Sony format just wasn’t on Amstrad’s radar.

The Sony system was only popularised by the Macintosh, which wasn’t released until January 1984. Previously the Sony disks had only appeared in a number of more obscure products and it wasn’t an obviously winning format. It hadn’t had a chance to take hold of the market before key design decisions were being taken about the Amstrad drives. The CPC was an early adopter of this type of disk and it was more just chance of timing that Amstrad went in that direction.

There were not huge consequences to this decision (other than the disks being somewhat more expensive) since the CPC was a proprietary system that did not particularly benefit from compatibility with the rest of the industry anyway. The CF2 stored 180KB per side, which was comparable to the 5.25” disks it was replacing at the time of release. All CF2 disks were double sided and could be flipped to store an additional 180KB on the reverse side, providing 360KB in total. The Sony 3.5” format did exceed this though, achieving this capacity on a single side and would soon offer higher capacities. The CF2 technology received an upgrade but ultimately did not keep pace with Sony.

Later Models

The CPC 464 was complimented a year later by the CPC 664, introduced in April 1985. This was essentially the same machine in a new case but featured an integrated CF2 disk drive instead of a cassette recorder, which was similar to the DDI-1 add-on. There was also an updated ROM with a number of bug fixes.

The mid 1980s was a cross-over point when more UK users were beginning to demand disk drives as a standard expectation but the devices had still not reached the commoditised low price levels they eventually would, leaving space remaining in the market for the now extremely cheap cassette storage. The 664 was added to the range as a new option at a higher price of £339 and £449 for monochrome and colour respectively. It did not replace the 464, which was still selling well and continued much as previously.

The internal Amstrad code name for the CPC 664 was IDIOT - Includes Disc Instead Of Tape.

In only June of 1985, the 664 was upgraded to 128KB of RAM and released as the 6128 with a much more subdued case design. This was at the request of US distributors who felt this was a better match for professional expectations in that market. The 664 was dropped from the range shortly afterwards, having been in production for only around six months, leaving the 6128 as the only disk offering. To the irritation of 664 buyers, the improved 6128 was cheaper at £229 and £399 for the two models respectively.

The Amstrad 464 Plus and 6128 Plus evolved the range with improved hardware including a significantly expanded colour palette of 4096 colours with 31 on-screen at any one time. The system now had finer hardware scrolling resolution which was easier for game developers to make use of and hardware sprites. As previously the 464 Plus used tape and the 6128 Plus was disk based. All very good, the only problem being this refresh was released in late 1990 by which time the CPC had lost its lustre and buyers had their eye on more sophisticated machines that were also getting into Amstrad’s price bracket.

Image Credits: Amstrad CPC 464, by Bill Bertram, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.5 Generic license; CF2 Disk, by Inkwina, Public Domain